At the start of my career as a physiotherapist, there was a distinct biomechanical and pathoanatomical focus to my clinical reasoning process with patients. It required that I understand and memorize distinct patterns of movement at each joint, clinically test each of these joints and then provide treatment on this basis. For example, there were 14 different tests for the sacroiliac joint to determine a specific lesion and these tests required the ability to palpate incredibly small movements. Although many of my patients improved with this treatment approach, others clearly did not fit into this model. Gurus would suggest that failure was due to a lack of experience, the wrong direction with mobilization or the inability to have the gift of feel. I became increasingly aware of other factors that influenced a patient’s pain experience with injuries and began to consider psychological and social components of the patient’s presentation that might influence their outcome. Ironically, with this expansion of clinical factors, my treatment and assessment for injuries became ironically simpler despite an increasingly complex clinical picture.

At the start of my career as a physiotherapist, there was a distinct biomechanical and pathoanatomical focus to my clinical reasoning process with patients. It required that I understand and memorize distinct patterns of movement at each joint, clinically test each of these joints and then provide treatment on this basis. For example, there were 14 different tests for the sacroiliac joint to determine a specific lesion and these tests required the ability to palpate incredibly small movements. Although many of my patients improved with this treatment approach, others clearly did not fit into this model. Gurus would suggest that failure was due to a lack of experience, the wrong direction with mobilization or the inability to have the gift of feel. I became increasingly aware of other factors that influenced a patient’s pain experience with injuries and began to consider psychological and social components of the patient’s presentation that might influence their outcome. Ironically, with this expansion of clinical factors, my treatment and assessment for injuries became ironically simpler despite an increasingly complex clinical picture.

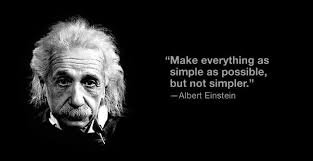

So why are things simpler? Sometimes it is worth looking at ideas outside of the physiotherapy world for answers. Eric Berlow is an environmentalist who does a TED talk on complexity to simplicity when dealing with endangered species. Berlow notes that complex problems do not always have to lead to complex solutions. He suggests that in order to understand a complex problem we view all the known information and how it is linked together. When attempting to intervene and cause change, we step back and look at the complex web of interaction and the big picture. This often leads to the identification of a few key modifiable factors to a problem and changing these leads to the greatest likelihood of success. In essence, embracing complexity leads to simple solutions.

This model is very relevant when it comes to many aspects of physiotherapy. For example, low back pain is an incredibly complex entity that has many known biological, social and psychological components. Collection of excessive information leads to red herrings that cloud decision making and difficulty weighting the importance of conflicting test results. Remember the example of the 14 SI joint tests? How do we make decisions when half of the tests are positive and the others are negative? Even if a clinical test is positive, how does it influence our interventions? In the case of the SI joint, would a positive test lead to a specific treatment that would result in superior outcomes for our patients? Are these findings reliable? I would argue that for the most part, these tests were unreliable and did not lead to a specific intervention that improved outcome. If we attempt to examine all of the spine with a multitude of biomechanical tests, we become lost and confused in trying to intervene. Unfortunately, this model of complex minutia is still taught (here) despite clear evidence that palpation of the spine is not particularly reliable, treatment is not specific (ref) and likely does not matter (ref).

“Simplicity from an evidence based perspective requires a deep understanding of the literature in order to identify those variables that will actually impact patient outcomes”

If we focus on specific tests that lead to an intervention that can improve outcomes, we can significantly improve our probability of success. For instance, depression, fear avoidance beliefs and catastrophization are variables that are easily tested and are known to worsen outcomes. There is limited evidence to suggest we can specifically palpate movement at a spinal segment but we can test for general hypomobility and hypermobility with some evidence that this can influence our choice of manual or exercise based interventions. This would be a much simpler than specific movement testing and stability testing of each joint in the lumbar spine. In essence, the lens with which the problem is viewed from has widened to see a broader clinical picture but in the process it was necessary to sift through extraneous testing minutia that was either irrelevant or unmeasurable.

This model of simplicity should not be confused with a lack of effort or deeper knowledge on the part of the clinician. On the contrary, simplicity from an evidence based perspective requires a deep understanding of the literature in order to identify those variables that will actually impact patient outcomes. It also requires that we be able to step back and look at the forest through the trees and understand the “Big picture” of the patient standing before us. Humility is also necessary as embracing this model requires that the clinician question some of the inaccuracies of previous clinical reasoning systems and constantly adapt to new evidence that can help sharpen our clinical assessment. This humility is the acknowledgement that we are often very far from fully understanding both what causes people’s pain and why our treatment interventions are effective. Becoming comfortable with the unknown and recognizing the large gaps in our understanding of our patients’ presentation is integral to the idea of a simplistic approach.

Why are we enamoured with complex models that may have limited evidence to support their usage in clinical practice? That’s a topic for a future blog. In the interim, I’d love to hear others thoughts on the idea of simplicity and would suggest that other clinicians regularly reflect on their practice patterns. Are the questions and tests we perform truly providing useful information that aids in improving clinical outcomes or are they just clouding our judgement and leading us astray from those things that are really important?

Author: STEVE YOUNG, BSCPT, BA